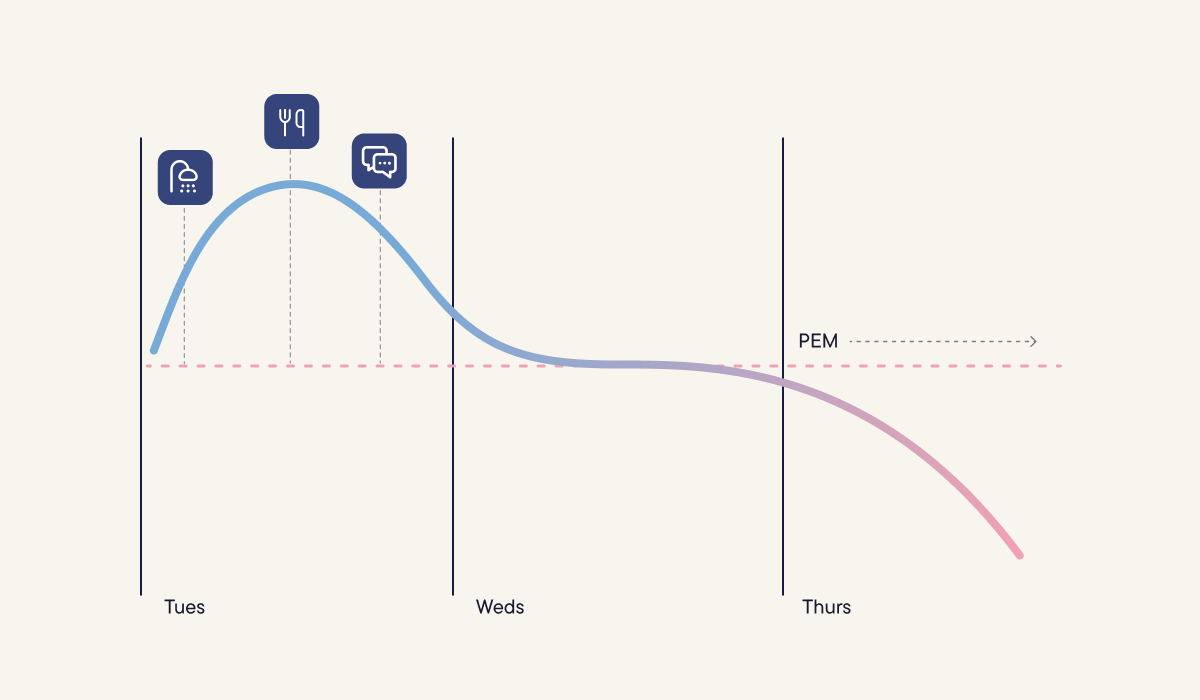

If you live with a complex chronic illness, you might recognize this pattern: some days you feel a bit more “OK". You decide to do something, maybe take a shower, cook a meal, or see a friend. At the time, it feels manageable.

Then a day (or two) later you're completely wiped out. You can barely move. Your brain isn't working. Everything hurts. And you are lying there thinking: what is happening? Why do I feel so bad?

If this sounds familiar, there's a name for what you may be experiencing: post-exertional malaise, or PEM.

PEM is widely misunderstood, and it can be both confusing and hard to recognize, even for people experiencing it.

This guide will help you understand what PEM is, how to recognize it, and (most importantly) what you can do about it.

What is post-exertional malaise (PEM)?

PEM is a worsening of symptoms and/or the onset of new symptoms after exertion that is delayed by hours or days, feels out of proportion to the activity, and involves a longer-than-expected recovery.1

Here's what this means:

- Exertion does not just mean exercise. It can be anything that uses energy:

- physical activity (walking, showering, cooking, cleaning)

- cognitive effort (concentrating, decision-making)

- emotional stress (difficult conversations, anxiety, excitement)

- social interaction (spending time with others, phone calls)

- Delayed means the symptoms come later. You might feel fine, or even energized, while you're doing the activity but feel much worse 24-48 hours later.

- "Out of proportion" means the response doesn't match the activity. A 30-minute walk usually doesn't leave people bed-bound for two days. But if you have PEM, it can.

- Recovery takes a long time. It can take days, weeks, or longer for symptoms to settle.

PEM is recognized as a key feature of the condition Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), but it also happens in Long Covid, Fibromyalgia and other complex chronic illnesses.[1,2]

What PEM feels like

PEM is not “being tired.” It can involve:

- a sudden drop in physical ability (heavy body, weakness)

- brain fog (trouble thinking and concentrating)

- pain (aches, headaches, flu-like feelings)

- sleep disruption (sleep that’s unrefreshing, even though you’re feeling exhausted)

- dizziness or heart symptoms when upright (palpitations, near-fainting)

- sensory overload (light and sound feel too much)

- digestive issues (nausea, loss of appetite)

- temperature dysregulation (hot flushes, chills, or struggling to warm up)

Not everyone experiences all of these symptoms, and they can vary from person to person. Here’s how two people on our team describe their experience with PEM:

”It feels like being shut out of your usual self. The same person is here, but my ability to participate in life is not available.”

“So I can cope with around 10 hours a week of increased activity or sort of concentrating… But if I take on any more, or there’s something unpredicted about my week, then I can really suffer afterwards… And then a couple of days later it really hits me and I literally can’t get out of bed.”

Why PEM is so hard to recognize (and so easy to trigger)

- It's delayed: You can do something on Tuesday, feel fine, then crash on Wednesday or Thursday. This makes it hard to see what caused it, and easy to repeat the same trigger.

- Small things add up: Think of energy as a daily budget. Small tasks can stack up, and trigger PEM, even if nothing felt big at the time.

- Your limit changes: Your daily energy budget isn't fixed. Sleep, stress levels, hormones, infections, and cumulative activity over previous days can raise or lower your threshold. What felt manageable yesterday might be too much today.

- Adrenaline can hide it: On stressful or emotional days, adrenaline can give you a temporary boost and help you push through. It's like a bank overdraft. It gets you through the moment, but you may “pay it back” later with a bigger crash.

A note on "Spoons": You may have heard of "Spoon Theory", which is a simple way to explain limited energy. You start the day with a certain number of "spoons" (units of energy), and different tasks use them up at different rates.

The spectrum of PEM

PEM exists on a spectrum. At the most severe end, even tiny amounts of exertion can cause a major worsening. That can include sitting upright, eating, speaking, light, sound, touch, or even having someone in the room. People at this end may need near-total rest and very careful control of stimulation.

At the milder end, more day-to-day life may be possible. Someone here might be able to work part-time from home and manage light household tasks most days. But larger activities such as going for a going for a run, attending a wedding, or taking a weekend trip could cause a crash.

Understanding this range of triggers is important because it reminds us that PEM isn't one-size-fits-all. What works for managing it will vary significantly based on which activities bring on symptoms.

Not all symptom worsening is PEM

Feeling worse after doing more isn’t unique to PEM. Many conditions can flare when you exert yourself, but the pattern is usually immediate: symptoms show up during the activity or soon after. The key difference is timing: many illnesses are “pay-now,” while PEM is “pay-later.”

Take asthma as a contrast. Exertion can trigger breathlessness or chest tightness during or shortly after activity, and symptoms often improve with rest and inhalers.

We’re still learning exactly what drives PEM biologically. But clinically, the signature pattern is consistent: a delayed crash after some sort of effort, followed by a slow, drawn-out recovery.

For a deeper dive into the science behind PEM, you can listen to our Make Visible podcast episode on exercise and PEM with Professor Todd Davenport, a leading researcher in the field.

The emotional toll of PEM

Living with PEM can be emotionally exhausting as well as physically disabling.

One day you're "fine enough" to do something small, and then days later your body pulls the floor out from under you. That loss of predictability means it's easy to start questioning your own judgment and can really shake your sense of self-trust.

When the future feels uncertain or risky, your nervous system can stay on high alert. Even on better days, there may be a constant tension, like you’re always calculating and bracing for a crash. It’s hard to truly relax or feel content when part of you is always watching for what might push you past your limit.

PEM can also be very isolating. Other people may only see the hour you managed, not the days-long crash that followed. And in healthcare settings, it can be hard to get this pattern recognized because PEM doesn't show up on standard tests, and it may not be something every clinician is trained to look for.

Managing PEM through pacing

Once you're aware of PEM, you can start learning to how manage it. There’s currently no cure for PEM, but many people find pacing (or energy management) helps reduce the risk of triggering it.1 Pacing means changing what you do and when you rest so you stay within your energy budget as much as possible.

Pacing has two parts: rest and reducing load. Rest is not just “stopping when you’re exhausted”. It means resting early and making sure your rest is truly restful, for example by keeping it low-stimulation and as calm as possible. Reducing load means adapting activities so they take less out of you, for example by sitting instead of standing or doing things in smaller chunks.

Because PEM is delayed, pacing by "feel" alone can be hard. Wearables like Visible can help shorten the feedback loop by giving you earlier signs that your body may be under strain and need rest. Over time, spotting patterns (like rising exertion, poor recovery, or repeated “too much” days) can help you make small changes sooner. These strategies can reduce the risk of PEM and help you keep more stability in your day-to-day life.

We’ll be sharing a deeper guide to pacing strategies and how Visible helps with them soon. In the meantime, you can find a step-by-step pacing guide in our Help Center.

Moving forward with PEM

If this all feels familiar, it isn’t a sign that you’re lazy, unmotivated, or “out of shape". It’s a sign that your body is unwell, and that activity has a different impact on you right now.

Living with PEM can be incredibly difficult. But as you start to recognize your patterns and practice pacing, things often become more manageable. There is often a learning curve, and setbacks are common. Over time, though, many people find they can reduce the yo-yo cycle and build days that feel more predictable and liveable.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and general informational purposes only. Visible is not a medical device, and does not provide medical services such as diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention or treatment in relation to any disease or medical condition. It is not a substitute for the advice of a medical professional based on your personal circumstances. You should always consult a doctor before making any medical decisions.